Designing meaningful products in the age of AI

Introduction

As head of product at Unscripted Photographers—a software company building products that help photographers turn their passion into a successful business—I've had a front-row seat to how AI tools are transforming our industry. My background spans about 10 years working as a graphic designer, UX designer, and web developer for agencies and small companies, which has given me perspective on how dramatically our profession has shifted in recent years.

AI tools and workflows are becoming ubiquitous in professional design practice. This technology is amplifying our capability in remarkable ways, but it's also eroding some of the human skills that make designers valuable. This article explores how AI is reshaping three fundamental aspects of design work—agency, taste, and capability—and offers a framework for navigating this transition thoughtfully.

The Changing Nature of Design and Work

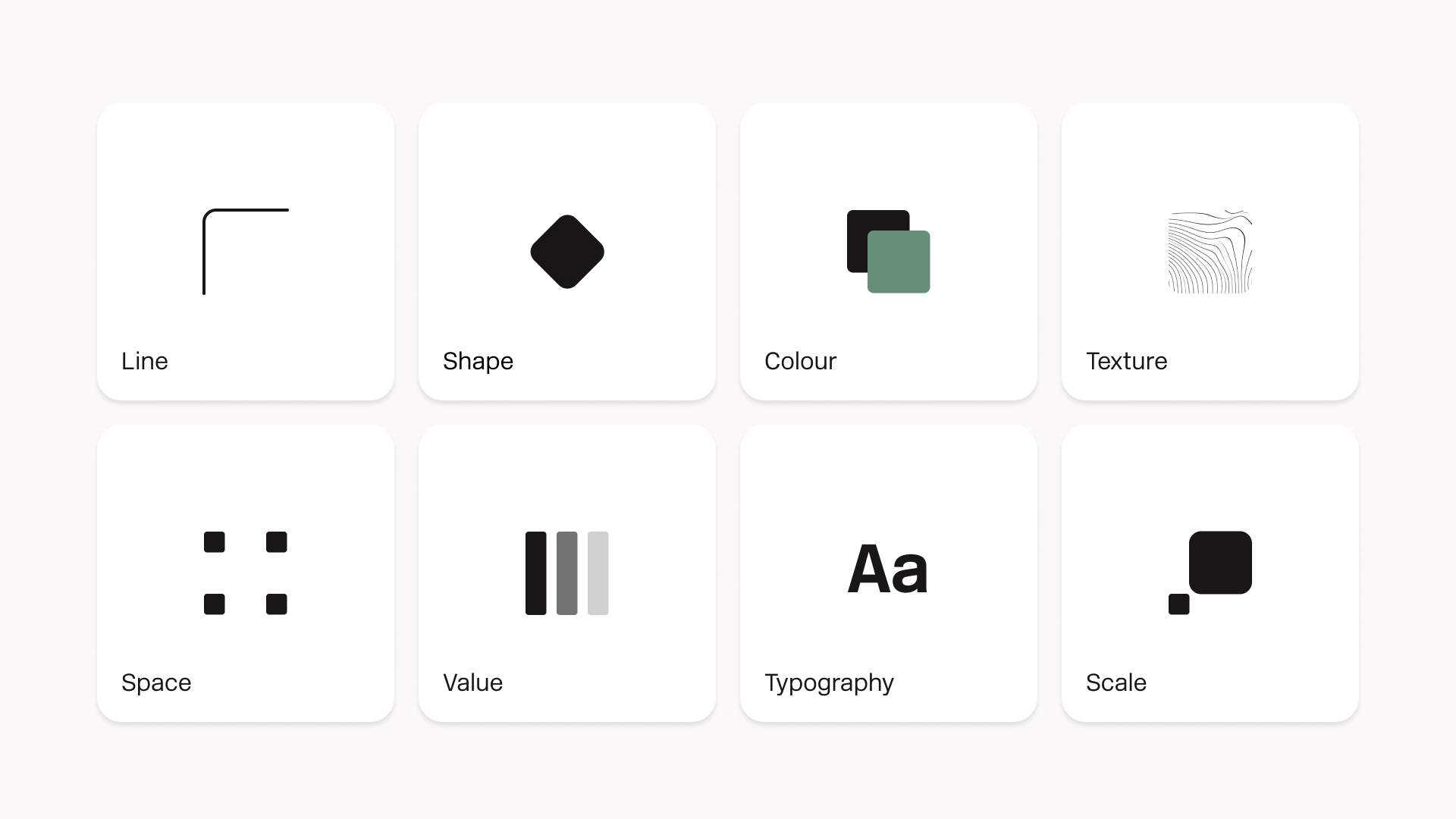

When I started my design career as a graphic designer about 12 years ago, the focus was on mastering the core principles of visual design and applying the right combination of those principles to your work. By the time I began freelancing, more and more graphic designers were being pulled into UI design as web and mobile products surged in popularity. It was a natural transition, as UI design benefitted greatly from strong foundations in visual hierarchy, layout, and typography.

But as digital products became more complex and behaviour-driven, design practice expanded beyond aesthetics. Teams needed to understand user goals, flows, conversions, and patterns in behaviour. As a result, demand for UX designers exploded.

UX had a different lineage, emerging from research methods and philosophies like human-centred design and design thinking. The focus was on making products useful, usable, and satisfying—qualities that were becoming a strategic advantage in an increasingly crowded market.

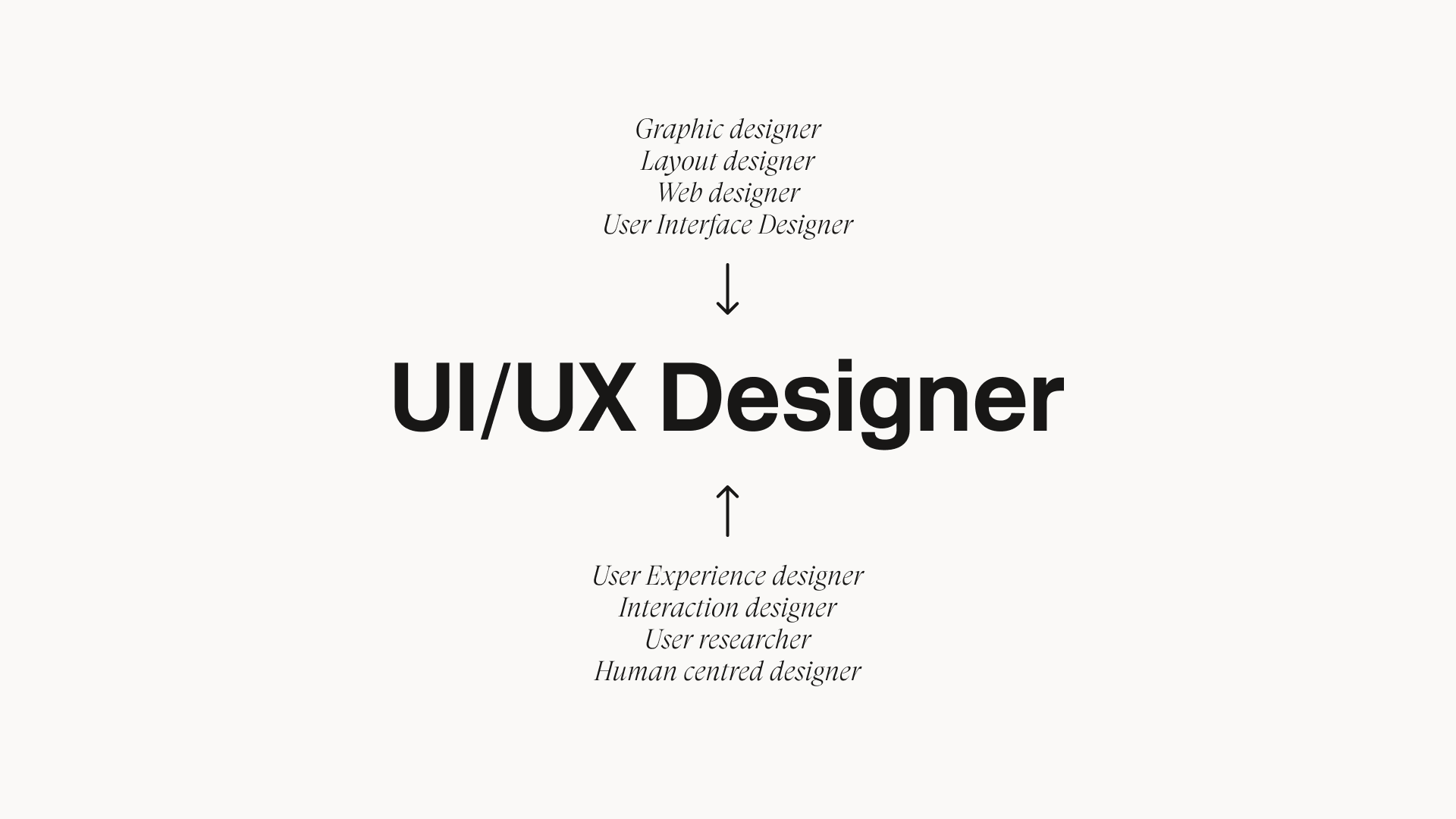

The Hybridisation of Design Practitioners

As my career progressed, I witnessed the rise of the hybrid UI/UX designer. Businesses understood the value of both disciplines but often lacked the capacity to support them independently. UX designers needed enough visual design skill to prototype effectively. UI designers had to inform their decisions with research, context, and best practice. The roles converged.

These hybrid roles really came into their own when Agile software development rose in popularity. Agile's emphasis on small, fast iterations and constant collaboration meant teams needed designers who could do more than stay in their lane. UI/UX hybrids were suddenly expected to move fluidly between research, prototyping, and high-fidelity design so they could keep pace with engineers.

In practice though, Agile teams often only moved as fast as their most constrained specialists—usually overburdened engineers dealing with tech debt, bugs, and infrastructure maintenance. Hybrid designers felt this pressure too, juggling research, design delivery, and expanding design systems. This was the landscape when consumer AI tools first appeared.

The Arrival of AI

AI rapidly shifted from a novel curiosity to a widely used means for boosting individual productivity. Naturally, engineering—usually at the forefront of emerging technologies—was the first business function where widespread adoption happened.

At Unscripted, we witnessed first-hand the dramatic increase to delivery speed that our engineers were able to achieve through tempered use of AI. Engineering, typically one of the biggest and most expensive bottlenecks in a product company, suddenly started moving a lot faster.

A big part of this quick and widespread adoption was the level of sophistication and accuracy these early models showed when generating code. Microsoft Copilot and ChatGPT 3.5 were trained on vast quantities of software data, and their early capability was a reflection of that.

In comparison, early image generation was extremely cursed. Early experimentation with visual design didn't yield useful results. Twelve months ago, these models were laughably bad at generating user interfaces. Now, you can generate a beautiful UI mockup in seconds.

The interface on the left in the image above was painstakingly designed by me 12 years ago—the first piece of design I was ever paid for when I submitted it to a design contest on 99designs for $300. We're now seeing the proliferation of sophisticated image and video generation technologies, and for those of us who have built careers on the back of our visual design skills, the emergence of these tools and their ever-increasing level of quality can be confronting.

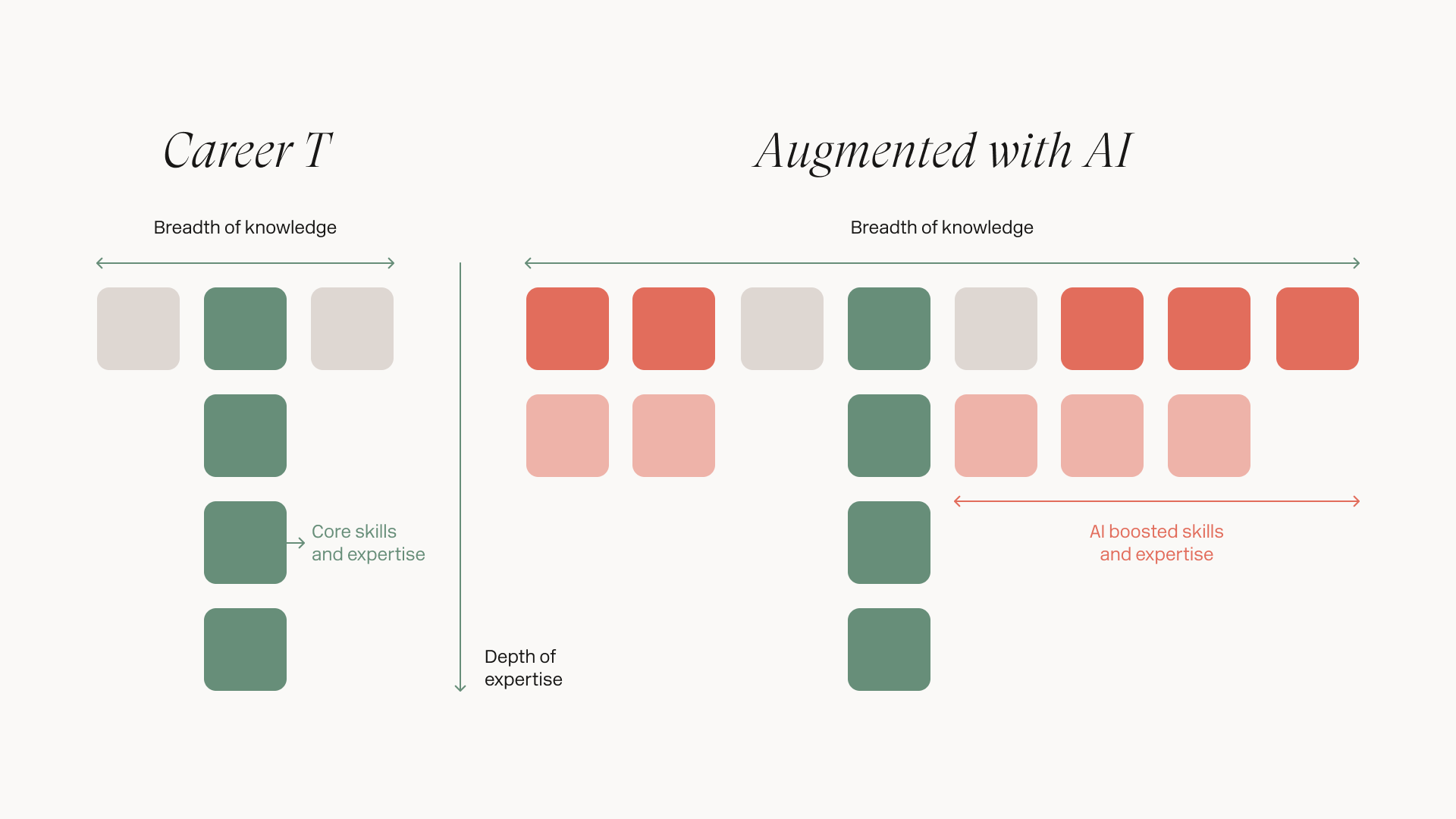

The Augmented T-Shaped Skills Model

We're in the middle of a major shift in what it means to work as a professional designer. AI tools are already reshaping how we develop skills, how fast we build them, and what "competence" even looks like.

Traditionally, design careers evolved in two directions: deepening your expertise in a specific craft area, or broadening your skills laterally into engineering, analytics, or business. Organisations—especially large ones—would traditionally seek out specialists with the deep expertise needed to address specific knowledge or capability gaps in their teams.

What we're seeing now is a broad augmentation of an individual's skillset, both in breadth and depth. AI is giving people the ability to complete tasks that once required collaboration across several specialist disciplines. This pattern is emerging across design, engineering, marketing, data analysis, and most knowledge-work domains.

Under the right circumstances, this leads to significant efficiency gains—something I'm seeing every day among the designers and engineers I work with. Those with meaningful experience are at an even greater advantage. They're able to leverage their knowledge and conceptual awareness to evaluate AI output more critically and steer it more effectively—dramatically increasing their output without an obvious dip in quality.

A Framework for Understanding the Shift

Recently, Ivan Zhao—the CEO of Notion—gave a talk at SXSW Sydney where he broke down the work we do as designers into three components: agency, taste, and capability. This framework provides a useful lens for understanding how AI is reshaping design practice, for better and for worse.

Agency: The Erosion of Sense-Making

Agency is your freedom and ability to make decisions—but it's also your willingness to pursue ideas, explore possibilities, and maintain momentum. In the three years since ChatGPT 3.5 was first released, AI tools have become embedded in how we work, and they're starting to eclipse traditional forms of research and inquiry.

Before this, tackling a tricky design problem—like fixing a poorly performing mobile onboarding experience—involved a pretty manual, messy process:

Googling "best onboarding examples" and opening 10 questionable articles

Hunting down case studies from competitors, pouring over screenshots and trying to reverse-engineer their flows

Flicking through UX books you hoped might be relevant

Checking Behance, Dribbble, and Pinterest for patterns or inspiration

Most importantly, discussing your thinking with colleagues and getting pushed, questioned, or challenged

It was slow, imperfect, and fraught with missteps. But that friction was what strengthened your judgement. Manually separating valuable insights from noise forced you to reason, compare, evaluate, and decide.

Now these models are exceptionally good at not only collating this information for you but applying that information to your specific context. You can upload screenshots of your problematic onboarding and it can immediately diagnose problems comprehensively and accurately. It's extremely convenient—but it removes the uncomfortable parts of research that actually build our critical thinking. When the tool does the sifting, interpreting, and prioritising for you, you lose the chance to develop those muscles yourself.

The more we come to rely on these efficiencies, the more our sense-making skills risk atrophy. These aren't just "design skills"—they're foundational judgement skills that support everything from product strategy to team leadership to decision-making in everyday life. Researchers are already raising concerns about cognitive offloading: the more frequently we outsource reasoning to automated systems, the less capable we become of forming strong, well-rounded conclusions on our own.

Taste: The True Differentiator

As Elizabeth Goodspeed, It's Nice That US Editor-at-large, observed:

"What makes AI imagery so lousy isn't the technology itself, but the cliché and superficial creative ambitions of those who use it."

Taste is the designer's true differentiator—the part of our work where there is no shortcut. It's a combination of your unique perspective and the preferences you've either actively developed or passively picked up in your broader cultural context. As designers, taste—and in particular, good taste—is what enables us to navigate a vast sea of possibilities and then select and combine elements in ways that result in interesting, unique work. It is one of the most significant advantages a professional designer has in their toolkit, and it can take years or decades of actively seeking out a wide variety of diverse inputs to refine it.

The gap between your taste and your ability to execute is responsible for some of the most acute creative frustration. People who have great taste in abstract art, music, or poetry struggle to create because their sense of what "good" looks like develops long before their technical ability.

It's tempting to think that AI might help bridge this gap between taste and technical ability. If you can clearly articulate your taste, the technology that exists right now is good enough to help you express it—but it cannot help you develop it. It's a process of individual discovery and experimentation that helps you understand and articulate your taste. If you miss the messy, exploratory part of the creative process, your taste never actually matures.

The Photography Parallel

Photography is a prime example. Just a few decades ago, the process of taking and developing photographs required extensive training and access to expensive, temperamental equipment. Today, anyone with a smartphone can take a high-quality photograph. But despite the widespread access to this advanced technology, it is still difficult to produce a compelling photograph without a well-developed eye for composition, a deep understanding of light, and the intuition to find subjects that reflect your unique perspective. These are the hard-earned skills that are won through a cycle of creative inspiration and experimentation.

We're already developing an intuition for "AI flavour"—work that looks technically polished but feels hollow. Our ability to recognise it is rooted in taste, not technical expertise. I don't believe that all creative works generated by AI are inherently worse than human creative work. But I do think that AI will always produce uninteresting, pedestrian creative work without an engaged and tasteful human guiding the creative process.

As these tools get better, taste will matter even more—because without it, AI pushes you toward the most expected, generic version of an idea.

The Statistically Likely Trap

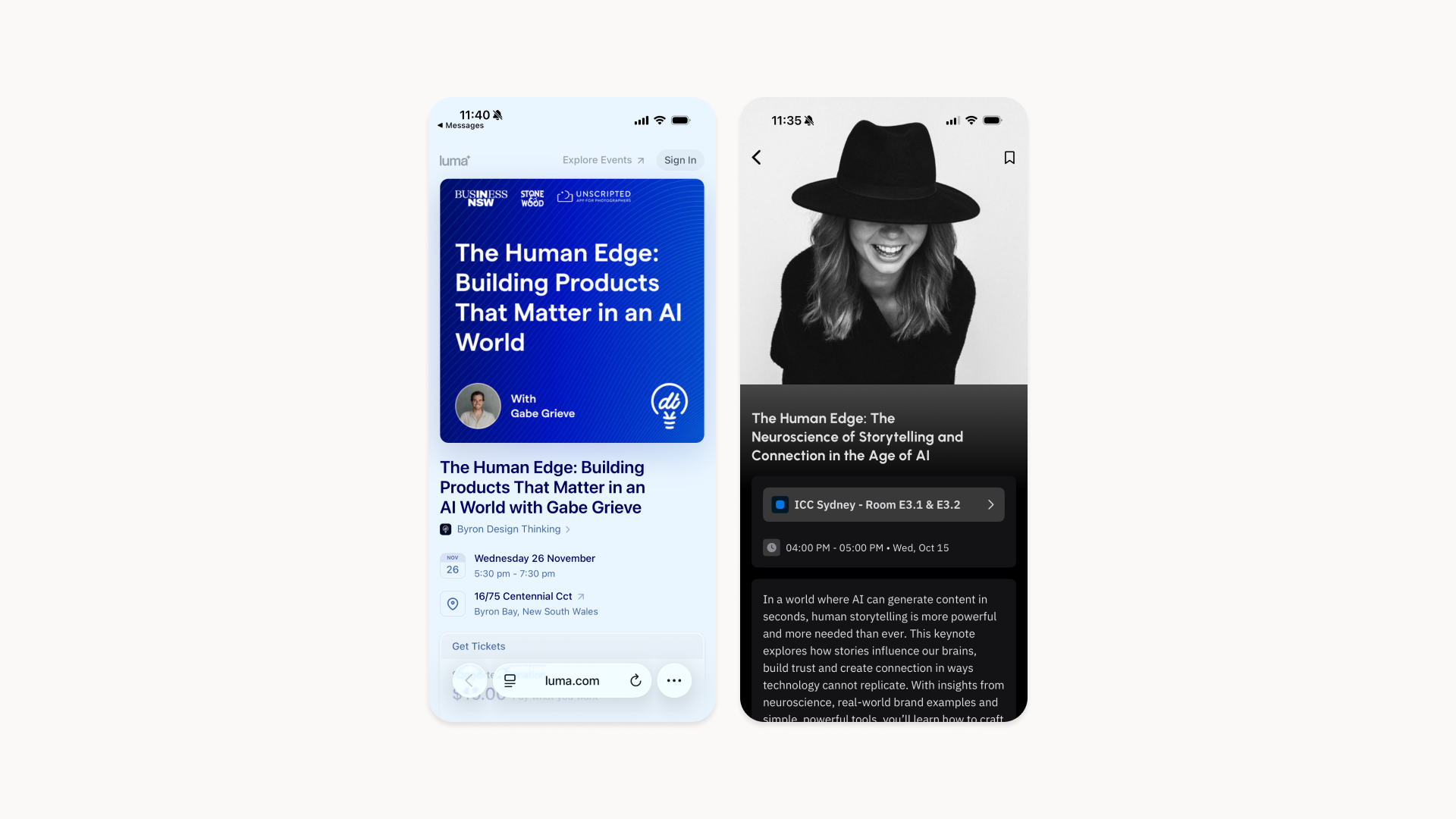

I was at SXSW Sydney when preparing a talk on this topic. I needed a title and was struggling to find time to craft something punchy. Naturally, I dumped the concept into ChatGPT and asked for suggestions. I went with its first suggestion: "The Human Edge: Designing meaningful products in the age of AI."

When reviewing the SXSW talk schedule the next day, I discovered afternoon session titled: "The Human Edge: The neuroscience of storytelling and connection in the age of AI."

This example demonstrates how easy it can be for AI-generated creative work to pass the sniff test. If you come to rely on it too much for your creative work, you'll find that what you end up with are the most statistically likely ideas.

Capability: The Illusion of Competence

As Oisin Hurst observed:

"AI is to creativity what microwaves are to cooking."

Capability is defined as what you're able to accomplish with the skills you've developed and the knowledge and experience you've acquired. The ramifications for AI's impact on an individual's capability are immense. It expands the breadth of what we are able to execute on and the speed with which we are able to execute. For experienced designers, this expansion of capability stacks on top of taste and agency. But it can create dangerous confidence when that capability starts exceeding your experience and judgement.

These tools can create the illusion of competence, especially if you start relying on the capability of the machine to make up for your inexperience. This is where capability becomes dangerous—not because you can make more, but because you can make more of the wrong things, more confidently than ever before.

Producing high-polish work quickly is intoxicating. That dizzying sense of progress and achievement can lead to a strong feeling of momentum. Compounding that feeling is the fact that these AI interfaces are tuned to make your experience as pleasant as possible—particularly in creative contexts. They tend to be overly encouraging and optimistic about the quality of your ideas and will even reinforce your own biases to avoid sounding dismissive or harsh. While it's possible to mitigate these behaviours with careful prompting, often you don't want to—that positive reinforcement can feel motivating when you're building momentum on an idea.

The Isolation Trap

This can lead to a trap I've seen time and time again throughout my career—both in the agency world and the product world. People get tunnel vision when it comes to their own ideas, and they execute on those ideas in an echo chamber, completely ignoring the people those ideas are meant to benefit. Without the natural constraints of inexperience that once forced collaboration and consultation, it's now easier than ever to work entirely in isolation.

No-code or vibe-coding platforms like Lovable and Base44 are quick to market the idea that you can build and ship production-ready software yourself with no design or engineering experience. But this approach can be disastrous in product development. Working without input from customers, colleagues, or specialists rarely leads to success. At best, you produce something that perfectly reflects a flawed idea. At worst, you waste countless hours polishing something nobody will ever care about.

From an organisational perspective, the risk of optimising for individual speed and output is that we undervalue the slow, collaborative work that is essential for developing strong ideas. This has a tangible impact on the products you ship, as the meaning and significance of the work we choose to do is lost in the frenzy of cranking out as much as possible.

A Three-Stage Framework for AI Integration

The future of design isn't about resisting AI. These tools are not going away, and they are already profoundly changing the way we work. We need to navigate this transition in a way that keeps human judgement and meaningful collaboration at the centre of design.

The following framework breaks the design and build process down into three distinct stages—generation, formation, and summation—with guidance on where AI tools are most useful and where they might be a distraction or counterproductive.

Generation: The Importance of Real Human Contact

Typically when forming the early strategy for a feature or product, your goal should be to explore the opportunities available to you. Generative research methods like interviews, surveys, and co-design are best suited here as they help generate ideas and answers about which way to go.

All of this increased capability afforded by AI can be a major distraction from the thing that everyone should be doing when they first start discovering and building products—having face-to-face conversations with real customers. AI isn't particularly great at this.

The truth is, talking to customers can be deeply uncomfortable. Nothing crushes momentum and enthusiasm like feeling firsthand somebody's deep ambivalence to your idea. It can take a lot of time, you get ghosted frequently, and it can be extremely taxing emotionally. The temptation to fall into the "build it and they will come" mindset is very strong in the face of this discomfort, especially now that the "build it" part is becoming so trivial.

But as designers, this discomfort is essential. One of the hardest yet most valuable lessons I learned as a young graphic designer was to get used to harsh feedback—because you receive it in spades. On the flip side, there is no better validation for your ideas and potential solutions than seeing someone light up with genuine excitement. When I was doing agency work, few things were more satisfying than watching a client gain clarity about their own business through something we showed them—or having the realisation that an annoying constraint or piece of feedback had actually forced our work to be better.

Unlike an AI chat interface, real customers aren't incentivised to make you feel good—they're motivated by their own needs and experience. If you approach these conversations with genuine curiosity about people's real problems, pain, and past behaviour, the insights that emerge will profoundly shape your product.

Uncovering Deep Insights

Good user interviewing technique is aimed specifically at uncovering insights that are not necessarily readily available on the surface. A skilled interviewer is able to leverage their intuition, empathy, and contextual understanding to know when to lean in and out of the different tangents that emerge in natural conversation.

The process that goes into determining the framing of the interview should be rigorous. It should be stripped of bias, leading questions, and anything that might promote falsely positive responses. AI is excellent for this process. It can also be helpful post-interview for parsing transcripts for insights that may have been missed.

But the interview itself should be flexible. Designers should engage the participant in a way that makes them feel comfortable sharing their experience in detail. While the framing is always useful to return to, often the open-ended nature of well-written interview questions allows the most interesting and unpredictable insights to emerge.

This is the key benefit of gathering qualitative data in the generation phase. Collecting quantitative data in the form of surveys or feedback requests can be great for identifying and synthesising broad trends, but this is an inherently one-way process—you put forward specific questions and receive specific answers. The most productive interview sessions feel like there is an interplay between the inputs of the interviewer and participant, each building off the other to explore ground that neither may have anticipated.

The Limitations of Synthetic User Interviews

We are starting to see advancement in the technology of synthetic user interviews. This technology offers researchers the ability to speak with AI agents trained on large sets of specific behavioural and demographic data. Many startups in this space are quick to point to the intention-action gap in user research as proof that user research with real people is inherently flawed—and that models trained on behavioural data will give a much more accurate indication of whether someone will perform some future action.

While I don't want to dismiss this technology outright, I think it has significant limitations that make it impractical outside of very specific use cases—like companies serving hundreds of thousands or millions of diverse users who struggle to answer basic questions about their customers without expensive research initiatives.

The most obvious flaw is the removal of human elements from the process. So much of the way we communicate with each other is nonverbal. There is a popular study suggesting our communication comprises 55% body language, 38% tone of voice, and 7% the actual words we say. While this study is often misrepresented, it points to something we intuitively feel to be true.

AI models are trained on text-based data. Their output is designed to be structured, concise, and emotionless. Humans tend to relate their opinions and feelings with their lived experience. AI has no lived experience. It is an aggregator of experience.

While you could theoretically probe a synthetic user to relay its lived experience, my guess is that the results will be unconvincing and unmoving. When communicating with real customers, these narratives can provide points of inspiration that can genuinely motivate us. We are messy, unpredictable, and emotional beings—prone to being unsure of our opinions and even changing them in real time. As designers, we have to lean into our empathy, intuition, and inference to truly understand the pain points that are clearly being felt by customers, even if they have trouble articulating them.

Formation: Accelerating Execution Without Losing Direction

Once you've grounded your direction in real human insight, you move into shaping the idea. This stage is generally concerned with improving the usability of design. Once a direction is selected, methods more aligned with the formation of the idea are used—in particular prototype testing and usability testing.

AI can accelerate execution here—but it still can't tell you which direction is right.

Every time I work on a new project, I instinctively want to jump directly into Figma and start trying to translate my vision into something extremely high-fidelity that feels real and compelling. All traditional design training would tell you this approach is wrong. Working in high fidelity from the outset basically guarantees painful and time-consuming revisions when requirements shift.

But for those of us drawn to visual communication, this risky approach can have big benefits for getting buy-in on your vision and building momentum on your idea. In my agency experience, there were countless times when showing clients a compelling, high-fidelity mockup got them genuinely excited about our direction and gave them confidence in our ability to deliver. I was delighted to learn that this is how they do things at Figma.

Tools like Figma Make, Lovable, and others are incredibly useful for generating and iterating on high-fidelity prototypes quickly. They have automated most of the painstaking work that previously went into wiring up complicated prototypes for testing, and the time to generate and ideate on them is effectively reduced to zero.

You no longer need to sacrifice fidelity and visual polish in the interest of saving time in the formation phase of designing a product. I think these tools still have a long way to go before they are truly able to generate production-quality products, but in terms of convincing prototype testing, they are remarkable.

That being said, we should be wary of the familiar traps of over-designing and over-polishing when we are in the formation stage. Polished prototypes are great for getting buy-in on your vision, but they can be a distraction when you are trying to measure how your product might resonate with customers.

AI-Assisted Usability Testing

When it comes to usability testing, I think there is a strong case for taking advantage of widely available AI tools. The spontaneity of qualitative interviewing is essential for uncovering deep insights. But user testing is generally much more linear and more concerned with highlighting the friction and pain points that arise from unfamiliar UX patterns, weak visual priorities, and confusing interface elements.

AI is generally quite good at identifying these pain points. It has decades of UX best practice in its training data that it can leverage to make recommendations for design adjustments that will benefit the majority of your users.

If you are designing something for an extremely niche market or for a very specific demographic, there may very well still be a strong case for performing usability tests with real customers. But my recommendation would be to leverage AI to help get the obvious kinks out before spending the time and effort to organise, run, and synthesise user tests with real people.

Summation: Measuring What Matters

Once shipped, product performance can be measured against earlier versions of itself or its competition. The methods that do this are summative—usability benchmarking, A/B testing, analytics, feedback requests. AI helps us interpret the data, but only humans can decide what to do with it.

Measuring product performance can feel overwhelming when you're staring at a sea of dashboards, funnels, and charts. AI can't compensate for missing or poorly implemented tracking, but once the foundations are in place, it becomes an incredibly powerful tool for interpreting complex data at speed.

For us at Unscripted, one of the biggest advantages has been using AI to turn raw event analytics into clear, plain-language insights. Tools like Mixpanel or Google Analytics often surface dozens of charts that require training to fully understand. AI makes it far easier to unpack what those charts actually mean: where users are dropping off in a booking flow, which features correlate with higher retention, or whether a spike in churn is tied to a specific release.

Even though deep analytics usually sit outside the designer's remit, we still need to make design decisions based on data. And because dashboards can be misleading—through bad segmentation, incomplete cohorts, or visually persuasive but statistically meaningless trends—AI is especially valuable as both a sense-making and bias-detection partner. It can flag when we're over-interpreting small sample sizes, confusing correlation for causation, or misreading outliers as patterns.

None of this replaces the need for strong product intuition or rigorous experimentation, but it does dramatically reduce the time it takes to get from data to understanding. It allows us to strengthen the judgement behind our decisions and keeps us focused on what actually matters.

Key Takeaways

Across each stage—generating ideas, shaping them, and evaluating them—AI amplifies our work, but it cannot replace the judgement that makes design meaningful. As we navigate this transition together, there are three things to avoid and three things to lean into:

Avoid:

Skipping real conversations with users

Confusing polish for progress

Placing too much confidence in the competence of AI

Lean Into:

Uncomfortable friction that builds judgement

Critique and feedback from diverse perspectives

Lived human experience as the foundation for insight

Conclusion: The Centaur Model

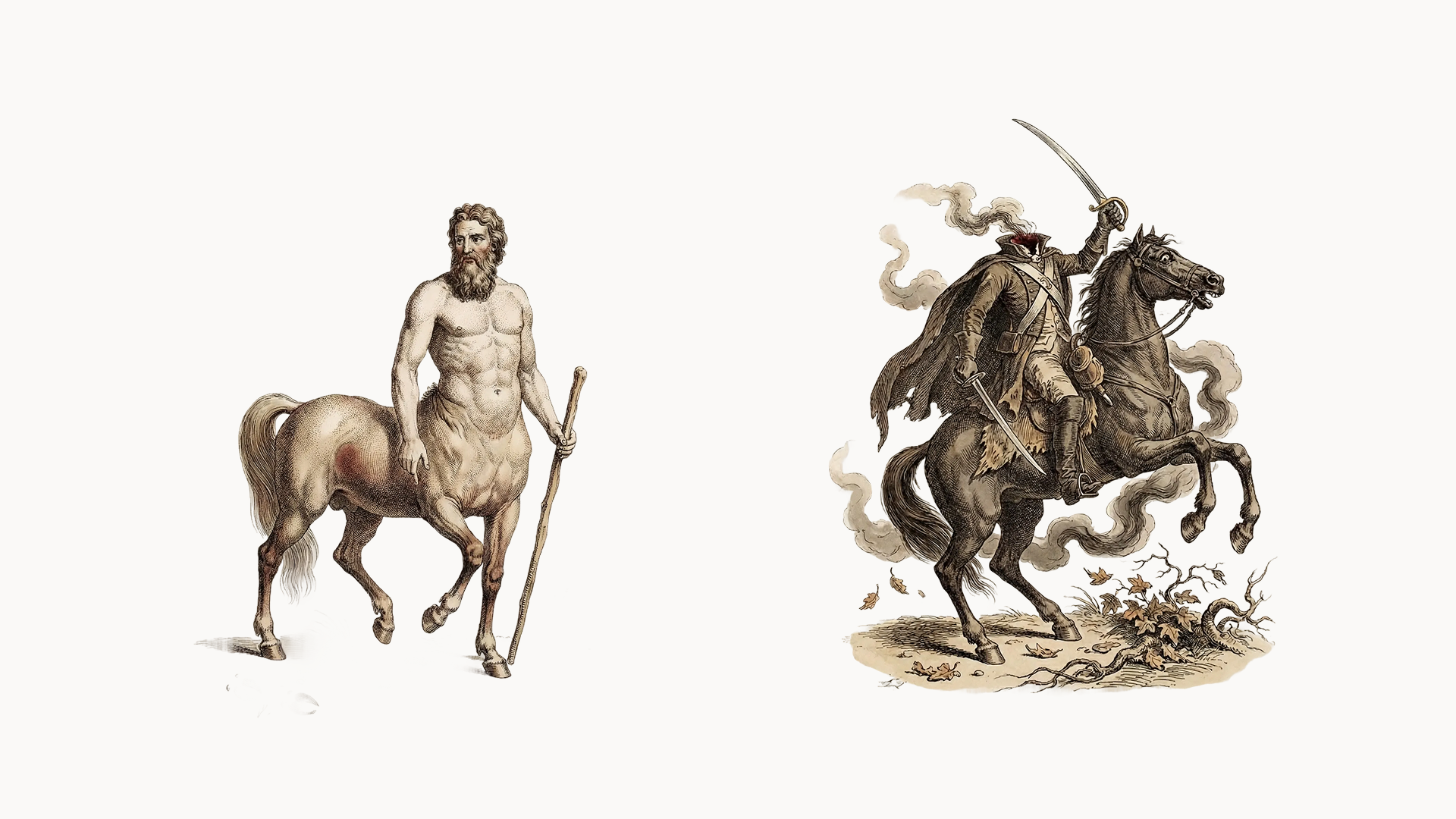

In the course of researching this topic, I came across the concept of the Centaur Model. Very briefly, the centaur model was conceived as a hypothetical state where humans and artificial intelligence or machinery are deeply interwoven—where human strengths like creativity, meaning-making, and ethical judgement are combined with machine strengths like speed, scalability, and deep knowledge.

I find this concept really appealing, and it makes me excited about what I could be capable of with continued access to technology that continues to develop at its current pace.

I don't know what the opposite of a centaur is called—for now, I'm just going to call it a headless horseman. The headless horseman is the worst of both worlds: a machine capable of incredible speed and clarity welded to a human body that slows everything down with laziness, bias, shaky critical thinking, and no taste.

Be a centaur, not a horseman.